Interiors are challenging subjects for photographers because viewpoints are restricted and lighting is usually inadequate and uneven. The use of a wide-angle lens is more or less essential, and some sort of artificial lighting may be required. Camera mounted flash may be adequate in relatively small rooms.

Our overall impression of a room is created by scanning the surroundings and assembling a composite mental image. Unfortunately cameras are much less sophisticated and see only what is in front of the lens at a particular moment. The best we can do to convey the sense of a room, rather than just a wall or a particular corner, is therefore to use a lens with a very broad field of view. Extreme wide-angle lenses, such as those having 120 or 180 degree field of view, exaggerate perspective and may create unacceptable distortion in the final two-dimensional image. This effect can be minimized by finding a viewpoint that keeps furniture at a distance and within the central half of the frame, and by ensuring that the camera remains horizontal.

Lighting is likely to be adequate close to windows, but may fall off sharply across a room. Contrast between bright and dark areas often exceeds the latitude of any film or sensor, so supplementary lighting must be used if loss of detail is to be avoided. Room lights create pools of lights separated by shadows, and also have a lower colour temperature than that of daylight. Flash should, wherever possible, be used in support of daylight. This means adopting the direction of the natural light to avoid creating multiple shadows, and adjusting output levels to fill the shadows without becoming the dominant light source. Flash bounced from a white ceiling or wall is generally preferable to direct flash because it is diffused and consequently gives softer shadows. When daylight and flash are mixed in this way, no colour correction filters are necessary.

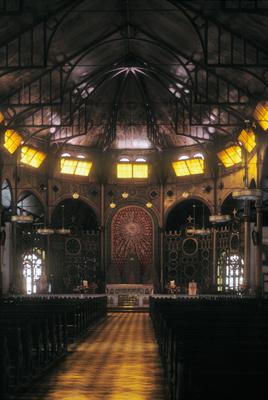

Very large interiors, such as those found in palaces and cathedrals cannot be directly lit by portable flash units, and are therefore usually photographed using available light. Light from windows and artificial lighting is usually designed to provide an attractive atmosphere although contrast may be high and windows may be overexposed. Use a tripod, a slow shutter speed and a small aperture to achieve adequate depth of field. If tripods are not allowed, use a fast film and hand hold the camera. A perspective control lens helps to avoid converging verticals in large interiors. However, they are heavy and expensive, and therefore likely to be carried only by the most dedicated architectural enthusiasts.

Very large interiors, such as those found in palaces and cathedrals cannot be directly lit by portable flash units, and are therefore usually photographed using available light. Light from windows and artificial lighting is usually designed to provide an attractive atmosphere although contrast may be high and windows may be overexposed. Use a tripod, a slow shutter speed and a small aperture to achieve adequate depth of field. If tripods are not allowed, use a fast film and hand hold the camera. A perspective control lens helps to avoid converging verticals in large interiors. However, they are heavy and expensive, and therefore likely to be carried only by the most dedicated architectural enthusiasts.

A final technique, which requires a certain amount of experience, is progressively to “paint” the interior by walking swiftly around the room to discharge a hand-held flashgun in numerous different locations. The camera must be tripod mounted so that the shutter can remain open for the time it takes to tour the room. A rapidly moving photographer dressed in dark clothing should not be visible in the final image. Lens aperture is determined by dividing the flashgun’s guide number by the distance from the subject that the flash is to be held. For example, with a flashgun having a guide number of 32 held 4 metres from the subject, an aperture of f/8 should be selected.

Ornate ceilings can be photographed by positioning the camera to look vertically upwards from close to the floor. A wide-angle lens will be required unless the ceiling is particularly high. Ideally, set the camera up on a tripod at eye level to compose the picture in the normal way. Very long shutter speeds can be used because there should be no disturbance from other people in the room. If this approach is not possible, try laying the camera on the floor, perhaps on a coat or cushion, directly beneath the centre of the ceiling. Framing is unlikely to be precise but can be adjusted at the printing stage.